3. Financing for Youth

Women Deliver Young Leader Alum Ali Kaviri speaking in front of a group at a Young Leaders workshop in Uganda. Credit: Women Deliver

When young people are supported with funding, they have the potential to challenge harmful norms, push for institutional and legislative reforms, and transform their communities. Yet young people face three significant barriers to equitable access to and distribution of funding, both at the global and national levels.

This chapter unpacks these three critical barriers and offers recommendations for equitable and trust-based funding practices that all grantmaking partners can adopt.

Towards Sufficient Funding for Youth Programs and Young People

Globally, official development assistance (ODA)37 for youth- and gender-focused programs, which most often goes to UN agencies, is quite limited within the scope of total development financing. In 2020, 5.56% ($7.6 billion) of total ODA from the top ten gender equality donors went to assistance programs that have gender equality goals and focus on young people aged 10-24. This is a vast underinvestment in a global population of 1.8 billion people ages 10-2438. Furthermore, while exact data on the proportion of ODA that goes directly to young people and youth-led organizations is not available, qualitative evidence suggests it is a tiny fraction of this already small total.

Based on research published in Resourcing Girls, “adults generally don’t feel comfortable with young people in true decision making power, and so a lot of the grantmaking ends up going to adult-led organizations and maybe they have special programming that’s devoted to youth. All of these things are important, but it’s not the same thing as having meaningful youth participation in terms of decision making about where funding goes and how that funding could best support young people.”39

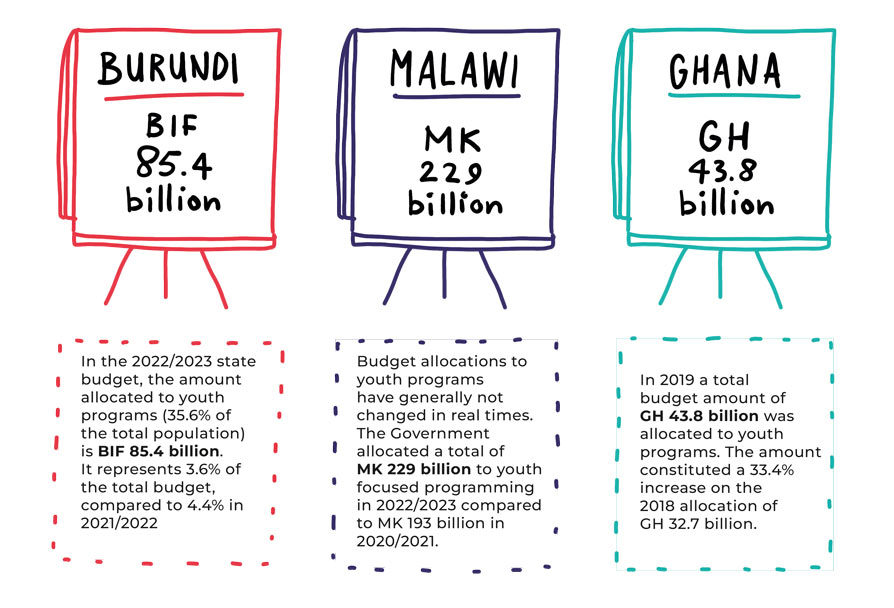

Meanwhile, domestic funding for youth-led organizations and initiatives is also quite limited in most countries. Governments face many competing priorities and are overwhelmed with what to prioritize. Often they prefer to fund tangible projects that their citizens can see, such as building roads, hospitals, health centers, and schools. On the other hand, alternative funding from local non-state entities is constrained by policy, socioeconomic, and environmental factors, such as performance instability. As a result, funding for youth programming or direct funding to youth primarily comes from non-domestic sources, such as organizations like Women Deliver. Unfortunately, scaling meaningful youth-led projects is often impossible, and the funding ends as soon as the development partner stops financing the work. Scaling and sustaining this work can only happen with national governments whose mandate is the development of their own country.

Image 3.2: Examples of domestic financing to youth in select countries

Global and domestic funding for youth should be restructured to promote sustainability of impact on young people’s contribution to society. A collaborative approach by grantmakers, governments, and non-state entities to the challenges faced by youth and the partnership arrangements in solving these problems should be reflective of the needs of society and how young people prefer to be involved.

Case Study

Domestic Funding for Youth-led Development in Rwanda[m][n][o][p][q][r]

The Rwandan National Youth Council (NYC), in collaboration with the Ministry of Youth and Culture, has proactively implemented equitable youth engagement initiatives with substantial funding. NYC coordinates all youth activities across the country, mobilizing and facilitating the formation of youth cooperatives through a structured network of executive committees.40 This allows youth representatives at all levels to advocate for their needs and, at the same time, accelerates the buy-in of both local and international organizations to fund youth initiatives directly. In 2020, the Ministry of Youth and Culture, in partnership with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), awarded 5 million Rwandan Francs each to 55 youth co-operatives in rural areas, successfully reaching some of the most vulnerable youth in the country and creating jobs for more than 3,500 youth across the country.

Furthermore, the Ministry of Youth and Culture has put in place a practical approach to securing domestic funds for youth initiatives through leveraging existing opportunities from other local and government institutions. In 2019, the Ministry of Youth and Culture negotiated with the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Ministry of Local Government to contract 153 youth-led companies for recurring road maintenance activities across the country. Each company receives monthly funds of 3 million Rwandan Francs, creating 7,760 jobs.

More efforts for domestic funding continue as NYC advocates for promising projects created by youth to secure funds from organizations such as the Business Development Fund Rwanda. Additionally, the Ministry of Youth and Culture regularly organizes competitions through Youth Connekt Africa and other local initiatives, where youth-led organizations can win grants to implement their initiatives while also receiving coaching and mentorship services to strengthen their management and leadership capacities. These initiatives have provided significant opportunities for youth to showcase their capabilities while contributing to their communities' development.

Equitable Funding Practices

According to the 2009 NESTA report Youth-led Innovation: Enhancing the Skills and Capacity of the Next Generation of Innovators,41 trust and support from adults, coupled with constructive feedback, are critical to promoting innovation and effectiveness in youth-led initiatives. However, funding relationships with youth are often not trust-based. This lack of trust often stems from the misguided assumption that youth lack the skills or expertise to carry out advocacy projects or make decisions, resulting in a push for capacity-building even in situations where it’s not necessary or helpful. Young people are still often seen as beneficiaries rather than agents of change. This lack of trust manifests in several ways throughout the grantmaking process.

Financial Exclusion and Eligibility Criteria

It is essential for all stakeholders to prioritize the need to facilitate and ensure equitable distribution and access to funding and investment to young people and youth-led initiatives. Before even applying for a grant, young people are systematically excluded from financial systems, making it challenging to have the necessary financial infrastructure, such as a bank account, to receive a grant. This is a significant hurdle for youth advocates, as this lack of trust is institutionalized to prevent youth from receiving and managing funds. In many cases, banking regulations prevent youth [h]from opening bank accounts, and funds are often held by other institutions rather than going directly into the hands of young people. According to the 2020 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report Advancing the Digital Financial Inclusion of Youth,42 nearly half of the young people around the world between the ages of 15 to 24 – a population of 1.8 billion – do not have a basic bank account at a formal financial institution. For instance, while 16% of young people in high-income countries are financially excluded, over 60% in Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean lack access to financial services[i][j][k][l].

Moreover, financially excluded people are more likely to be female, residing in rural areas, belonging to the poorest 40% of their respective countries, and less likely to have access to the internet or digital tools. This means the world’s most vulnerable youth are often locked out from accessing grantmaking mechanisms.

To be eligible to apply for a grant, many grantmaking institutions require an organization to have legal registrations in their country, such as recognition as a nonprofit organization. This can be an expensive and lengthy process that disqualifies nascent youth-led organizations and grassroots movements, as well as organizations working on politically sensitive topics that their government may oppose by blocking their registration. Furthermore, these criteria place undue importance on formalized registration processes, which is a standard that originated in the Global North and is rooted in colonial practices that inherently demonstrate a lack of trust in young grantees unless recognized by formal institutions that are deemed trustworthy, such as the government.

As a result, both globally and nationally, funding to young people often goes to a small, relatively privileged group of youth who are able to meet the stringent requirements described above and who have access to the networks and relationships that lead to these funding relationships. These funding practices exclude and further marginalized young people who live with disabilities, reside in rural communities, or lack internet access or proficiency in the English language. Additionally, given the vast diversity among young people, a small subset of youth cannot possibly represent the expansive views of all young people. However, by funding this subset, donors believe they have fulfilled their obligation to support youth and subsequently don’t look beyond the highest profile youth in a community or country. This approach can silence more marginalized youth who already face barriers to accessing opportunities.

It is essential to refine eligibility criteria for funding opportunities and consider the nature of local partnerships. This process can include research and evaluation of various factors that are context-specific within funding arrangements. Organic youth-led community groups, organizations, and initiatives have the potential to bring about desired community change. Community-based organizations (CBOs) can play a critical role in supporting young people in accessing funding opportunities and designing projects that are meaningful and relevant to their communities. Since they are positioned within the community and work closely with people from different backgrounds, CBOs are well-connected to the lived realities of many girls and women. However, most funding does not go to CBOs because of the lack of technical competencies required by grant makers and donors to be able to finance their programs. As a result, larger and well-established organizations who have the technical expertise to meet the funding requirements but lack community knowledge to implement or have access to the communities frequently receive funding that would have otherwise gone to CBOs with local expertise. This leads to INGOs or other non-local organizations implementing programs that may not truly address the needs of that community, especially the needs of girls and women.

Funding Priorities

Grantmaking institutions, rather than young people themselves, often determine the funding priorities for youth-focused grants and programs. Not including youth in the development of funding priorities robs them of their agency and results in funding priorities that are less likely to match their needs. Furthermore, funders frequently view young people as a monolith and neglect to account for the diverse backgrounds – and diverse needs – among this age group. These same principles apply to the grant review process, which often does not include those representative of the populations with whom a funder seeks to partner.

Based on research published in Resourcing Girls43, “Girls also said they needed to conform to an adult way of being, changing how they present themselves and their work to be accepted in the formal, adult world. The girls expressed frustration that some of the funders supporting their work did little to develop relationships of trust, and the resultant lack of proximity to their realities led to a deep chasm between girls’ work and the funders’ understanding of it. Girls also felt their agency and power was overlooked: they want to be included in the processes that seek to communicate their work, and more so to be afforded the visibility, representation and voice in decision making that is so critical to meet their needs.”

Designing grantmaking opportunities for youth with youth under the spirit of co-leadership should be a priority. Grantmakers should implement participatory methods to define the needs, solutions, and priorities in youth financing, as this provides an opportunity for trust building and increased contextual knowledge for all parties. The Norwegian Agency for Exchange Cooperation uses similar strategies where reciprocity is a core value between partners, with both the funding partner and the receiving partner declaring an interest and participating in the development of the project as a prerequisite for funding support. This process seeks to minimize power imbalances and promote collaborative agenda setting and shared interests.

In addition, designing grantmaking opportunities for youth with youth also enables youth to determine funding priorities. Such a model of supporting young people minimizes prescriptive and conditional financial support to youth initiatives and promotes innovation. This model has been applied by several foundations where innovative youth ideas are funded based on their relevance to society more than the priorities and interests of the resource holder. The Tony Elumelu Foundation44 is one such institution that has supported social entrepreneurship ideas by African youth.

There are many promising models for equitable and trust-based funding with and for young people. To tackle these issues in funding relationships with young people, donors and governments must recognize their power as resource holders and take steps to address this in their work with youth, enabling young people to negotiate financial terms, resources, and priorities without the fear of sanctions or economic exclusion. Resource holders must also increase funding to youth-led and youth-serving organizations to address the needs of the very large adolescent and youth populations globally.

Case Study

Grand Challenges Canada

Grand Challenges Canada has a peer reviewing model in which young people with lived experiences are invited to read, review, and comment on the applications they receive for funding. The young people referred to as expert reviewers are assigned to evaluate applications based on their innovation, accessibility, and affordability. They are asked to provide inputs based on their personal knowledge and lived experiences and are compensated for their time. The process is transparent and flexible in its approach to funding youth-led initiatives and organizations. One main eligibility criterion is for organizations to have a young person in a leadership role.

Grant Structures

Most funding to young people is awarded on a short-term project basis rather than long-term, unrestricted funding. When funders impose excessive reporting requirements or restrictions on how funds are used, this can limit the effectiveness of youth-led initiatives. Especially in advocacy work, where changes often happen incrementally over long periods, short-term funding makes the sustainability of an organization or an advocate’s work challenging, as well as undermines their ability to design and invest in effective long-term advocacy strategies. Additionally, funders, as the holders of financial resources, have more power in negotiating grant terms, making it difficult for young people to advocate for grant agreements that actually work for them.

One specific grant structure from ODA funders is localization, a development approach of funding domestic organizations that have expertise in their own communities. Unfortunately in the experience of the co-authors, as a result of this approach, national offices of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) often end up applying and competing for funding with domestic youth-led organizations. In order to qualify for local and youth-targeted funds, INGOs will apply for funding in partnership with national youth-led organizations. After the funds are awarded to INGOs, they often do not allow youth partners to access them. Instead, they rely on the youth-led organization to reach specific populations, such as rural or grassroots communities. As a result, localization funds often expose young people to financial predation, where their involvement is exploitative and facilitatory rather than empowering.

The complex bureaucratic processes within governments make it even harder for young people to engage and participate in these processes. For example, for young people to join a planning meeting at a government ministry requires approvals from many departments and technocrats. This makes it almost impossible for young people to get these approvals as the technocrats follow orders from above. Yet it is a crucial first step for young people to be involved in these planning processes to ensure their priorities are included in government work plans and budgets.

Rigid Monitoring and Evaluation Frameworks

Reporting processes imposed by donors have historically been used to monitor and even police the grantee’s use of funds, indicating a lack of trust in the grantee’s ability to manage funding responsibly. This is based on misguided assumptions about young people’s abilities and a lack of recognition of their agency as change-makers. Similarly, instead of using monitoring and evaluation tools as opportunities for learning and innovation or capacity development, they are usually focused on strict compliance and accountability. Additionally, these reporting requirements often require significant time to comply, which many young grantees and youth-led organizations cannot spare, thereby disqualifying them from these funding opportunities.

Resource holders need to create context-specific capacity assessment frameworks and monitoring, evaluation, learning, and reporting frameworks that promote equity in funding opportunities. This would include reevaluating funding and evaluation requirements to promote learning and growth over policing and compliance, as well as creating competence assessments and funding arrangements that encourage capacity development towards compliance rather than disqualification from funding. This process can, for example, include a case-by-case capacity assessment and plan for disbursing resources over time relative to short-term goals until the institutions are fully meeting the funding requirements for larger amounts.

Case Study

Women Deliver Small Grants to Young Leaders

Many of the challenges and solutions identified above reflect learnings from Women Deliver’s experience working with young grantees through its Small Grants, which is a component of the Young Leaders Program. Through the Small Grants Program, Women Deliver provides Young Leaders with the financial and technical resources they need to advance their own advocacy goals in their communities and contexts. Since 2014, Women Deliver has provided 213 Small Grants of $5,000 to $5,500 to Women Deliver Young Leaders and Young Leader Alumni, for a total of over $1 billion. Women Deliver’s current approach to grantmaking models many of the equitable practices described above, and Women Deliver plans to implement further changes to its grantmaking practices in the next iteration of the Young Leaders Program.

Designing the Funding Opportunity and Criteria

Women Deliver views Young Leader grantees as the experts in designing their projects. Women Deliver does not pre-select any specific advocacy topics beyond its overarching goal of advancing gender equality, allowing young people to set their own priorities rather than imposing Women Deliver's priorities on them. Additionally, the criteria for applying for a Women Deliver grant are minimal, making the Small Grants Program available to all applicants who are active members of the Young Leaders Program and have completed Digital University, which provides foundational advocacy training to all Young Leaders. On occasion, when there are funding criteria preferences dictated by Women Deliver’s funders, such as a geographic focus, Women Deliver communicates those in the call for applications. However, others that do not meet that preference are still eligible and welcome to apply.

Grant Application

Women Deliver holds two grant rounds each year within the Young Leaders Program, with applications open for 3-4 weeks for each round. During the application process, Women Deliver holds a Q&A session and one-on-one calls with Young Leaders to share the application and practical tips. Young Leaders can ask specific questions about their project ideas. Women Deliver’s Regional Consultants also advise Young Leaders by providing critical context-specific guidance.

The streamlined application asks for a project statement, a narrative on a Young Leader’s approach to measuring their success, a simple risk assessment, and an overview of any additional partners working on the project. Young Leaders also share a simple budget and a monitoring and evaluation framework, which they are free to design themselves. While the application has been simplified in recent years, Women Deliver plans to revise this application significantly by exploring submissions in multiple languages, video or visual submissions, or even application by interview.

Grant Application Review

Applications are reviewed by a diverse review committee made up of Women Deliver staff and Regional Consultants, as well as Young Leader Alumni who have been Women Deliver grant recipients in the past. A clear and concise set of criteria for application review is provided to the reviewers, which is also provided to Young Leaders in the application process. Each application is reviewed by 2-3 reviewers to ensure a diversity of perspectives on how the application meets the criteria. Scores are provided as a helpful review indicator, but applications are ultimately selected on a holistic review of the comments from reviewers, as well as to ensure demographic diversity in the total cohort of awarded grants.

Grant Structure

Grants from Women Deliver go directly to Young Leaders, so they do not exclude those who are unaffiliated with an organization and ensures that the funding is fully utilized by the individual. This also protects the grantees from financial exploitation, as described earlier in the chapter. Women Deliver is also flexible with the disbursement of funds by providing the funding to a bank account that is accessible to the Young Leader, including the account of a trusted friend or family member, or a PayPal account.

A limitation of Women Deliver’s approach to grantmaking is the limited funding amount, timeframe, and restricted nature of the grant. Currently, its grants are $5,000 to $5,500 for six months and must be used for a specific advocacy project. Young Leaders have shared in evaluations and feedback with Women Deliver that these aspects of the grant structure make it challenging for Young Leaders to develop and implement longer-term advocacy strategies, and there is often not sufficient length or funding to see advocacy outcomes. As a result of this feedback, Women Deliver is re-envisioning its grantmaking program in the next iteration of the Young Leaders Program, which will launch in Fall 2023.

Technical Support

Grantees have the flexibility to adjust their project budget as needed during their grant and shift or adapt their tactics based on the needs of the project and the realities on the ground. To support grantees in this process, Women Deliver’s Regional Consultants, based within the regions and contexts in which grantees are working, are available to troubleshoot and advise grantees, at their request. Additionally, Women Deliver staff and Regional Consultants hold a group orientation call for all new grantees, as well as individual calls to provide targeted feedback on their application. Individual interim and close-out calls are also held to support the Young Leader grantee during and after their project to adapt and distill learnings.

Reporting, Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning

Young Leaders provide an interim report at the halfway point in their project (three months) and a final report at the end of the project. Reports consist of six narrative questions, a budget report, and a report of their monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) results. Young Leaders design their own metrics for success in their projects and can utilize any MEL framework that is helpful for them.

Women Deliver acknowledges that given the size and length of the grant, this frequency and depth of reporting is excessive and could create a burden for Young Leaders to comply with these requirements. In the future grantmaking program, Women Deliver will develop reporting practices that are appropriate for the size and length of the grant and do not present a burden for grantees. This could include submission in multiple languages, verbal or interview reporting rather than written, and more informal reporting structures. Additionally, all reporting structures will focus more on learning and growth for the Young Leader grantee.

Citations

37. Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Official Development Assistance (ODA). Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm.

38. The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (PMNCH). (2023). 1.8 Billion Young People for Change Campaign and The Global Forum for Adolescents. Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://pmnch.who.int/news-and-events/campaigns/1-8-billion

39. Resourcing Girls. (n.d.). Resourcing Adolescent Girls to Thrive. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.resourcinggirls.org/

40. UNDP Rwanda. (2021, January25). Supporting Youth Economic Empowerment through Environment-related Businesses. Retrieved July 6, 2023, from https://www.undp.org/rwanda/news/supporting-youth-economic-empowerment-through-environment-related-businesses

41. Sebba, J., Hunt, F., Farlie, J., Flowers, S., Mulmi, R., & Drew, N. (2009). Youth-led innovation: enhancing the skills and capacity of the next generation of innovators. NESTA. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/youthled-innovation-enhancing-the-skills-and-capacity-of-the-next-generation-of-innovators

42. Resourcing Girls. (2023). Resourcing Adolescent Girls to Thrive. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/6256f3702c7c15d3ae5a2bf2/625fa359dced7e7ab171781b_Girls_Funding_Report_DRAFT.pdf

43. Tony Elumelu Foundation. (n.d.). Impact. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.tonyelumelufoundation.org/impact

44. Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Advancing the Digital Financial Inclusion of Youth. Retrieved May 2, 2023, https://www.oecd.org/finance/advancing-the-digital-financial-inclusion-of-youth.htm