2. Equitable Youth Engagement and Co-Leadership

Women Deliver Young Leaders collaborate at a regional workshop in Kenya. Credit: Brian Otieno

Around the world, young people are at the forefront of driving social change. Yet the current approach to youth engagement22 within gender equality and health advocacy spaces often stops at youth participation and consultation, seldom reaching the level of true youth leadership and ownership. Young people are rarely invited to be at the decision making table, and initiatives led by youth in their own right are often conceived to be marginal and have little or no participation by other age cohorts. However, this approach not only presents a missed opportunity for stronger gender equality and health outcomes but also denies young people their right to be in the driver’s seat of their future and the future of the planet.

Another shortfall of the existing approach to meaningful youth engagement is that youth are viewed as an undifferentiated and homogenous group, thereby ignoring the unique experiences, vulnerabilities, and needs of distinct groups of young people. In doing so, only the most privileged youth are able to engage in influencing gender equality and health policy. Yet the world’s most intractable gender equality and health issues often have a direct, consequential, and disproportionate impact on the most marginalized youth, particularly those that have intersectional vulnerabilities and multiple marginalizing identities such as adolescent girls, non-binary people, and those with differing abilities or belonging to minority groups. These influencing spaces must be created for and alongside the most marginalized youth to equitably engage youth in shaping global policies. With these youth leading in policymaking processes, the world will have more equitable health systems that can more effectively meet the needs of all populations.

This publication introduces a new approach to youth engagement, known as equitable youth engagement and co-leadership (EYECL), which addresses these challenges, as well as provides a clear guide on implementing EYECL within government and other advocacy spaces.

Key Terms: Equality vs. EquityIn discussions around social justice, the terms "equality" and "equity" are often used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings. Equality refers to ensuring that everyone has access to the same resources and opportunities, regardless of individual needs or circumstances. In contrast, equity recognizes that different individuals and groups may require different levels of support and resources to achieve the same outcomes. While equality results from a process, equity refers to the process itself. The intertwined principles of diversity and inclusivity lay at the core of an equitable approach. Narrowing equity gaps requires a commitment to allocating resources appropriately, tackling the underlying concerns and requirements of underserved and at-risk communities, and meeting young people where they are. |

Key Term: TokenismTokenism refers to the practice of including individuals from underrepresented groups in a way that is superficial or symbolic, rather than meaningful or substantive. Truly inclusive spaces embrace and celebrate diversity, whereas tokenism involves making performative gestures to appear inclusive. An example of this is selecting individuals based solely on their group identity (such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, or age) rather than their qualifications or experiences as a way to meet requirements without actually integrating diverse perspectives into design or decision making processes. As a result, tokenized youth may feel undervalued, disrespected, and not truly included. |

Key Term: IntersectionalityCoined by scholar and critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in 199023, intersectionality refers to the notion that individuals have multiple, overlapping identities (such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, ability, socioeconomic status, and more) and that these identities cannot be understood in isolation from one another. Instead, they are intertwined and can create unique experiences of oppression and privilege. |

Defining Equitable Youth Engagement and Co-Leadership

Equitable youth engagement and co-leadership is a transformative, intentional process in which young people, in all their diversity, are in positions of power and leadership alongside other stakeholders who may be traditional powerholders. This includes authority to design and create policies, programs, and initiatives, to make decisions and set agendas, and to hold leaders and decision makers accountable.

As part of this process, young people are provided with adequate and fair financial compensation in recognition of their expertise and energy, along with any technical or capacity support needed to be successful in their role.

Lastly, an enabling and inclusive environment is created such that young people are institutionally and structurally recognized as experts (not solely as representatives of an age group) and treated with respect as equals; young people are free to express themselves and their autonomy is respected without fear of retribution24; robust safeguarding ensures young people's mental, emotional, and physical safety; information is shared in a transparent, timely, and youth-friendly way; and equitable youth engagement and co-leadership is integrated into the design or structure of a process at its conception.

Key Term: InclusionCreating an inclusive environment goes beyond simply inviting individuals from diverse backgrounds to participate in activities or events. True inclusion requires intentionally addressing bias, discrimination, and exclusion in policymaking and program design. |

Equitable youth engagement should strive to "maximiz[e] youth potential and minimize[e] youth vulnerabilities… through programmes, learning and strategic partnerships.”25 Our approach to equitable youth engagement encompasses the inter related concepts of co-leadership, co-creation, and co-ownership.

Co-Leadership

Co-leadership is a leadership model in which two or more individuals share power, authority, responsibility, and influence. It can be particularly effective in situations where multiple perspectives are needed to solve a complex problem.

Feminist co-leadership is a variation of this approach that values collaboration, diversity, inclusivity, and equitable power distribution in decision making processes. Grounded in feminist principles, it requires a high degree of trust and communication and a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities to avoid confusion or conflict. When done right, feminist co-leadership can serve as a “practice of collective liberation,” but this requires being “sensitive and attentive to flows of power, spreading and weaving manifestations of power in ways that disrupt the linear and vertical concentrations of power that are at the foundation of patriarchal, capitalist systems of inequality.”26

Key Term: PowerPower refers to the exercise of potency in public spaces or formal systems of governance and accountability, such as political bodies, organizations, or social movements. However, decision making spaces often prioritize the needs of powerful actors over those of marginalized people, who may be excluded from these spaces altogether. Decision makers collaborating and engaging with young people must be cognizant of power dynamics that are rooted in multiple and intersectional identity markers, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, ability, socioeconomic status, and more, in order to adequately address power imbalances. |

Key Term: DiversityIn this context, diversity refers to the obvious yet often overlooked fact that young people are not a monolith. They occupy a wide range of intersecting identities, which include differences in race, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, religion, ability, socioeconomic status, and more. Promoting diversity requires actively embracing these differences and recognizing that young people’s diverse backgrounds, skills, and perspectives can help bring fresh ideas and foster creativity and innovation. |

While co-leadership is not a new concept, in the field of youth engagement, it is increasingly recognized as a best practice that not only gives young people greater agency over decision making and agenda setting but also leads to rich intergenerational relationships and mutual learning. Co-leadership can help young people decentralize traditional hierarchies and renegotiate power while uplifting each other and cultivating community. While building relationships – a key aspect of co-leadership – requires investing more time, it can ultimately make programs more effective by creating an enabling environment for collaboration, constructive criticism, and conflict resolution. Additionally, “when considering strategic vision and risk-taking, co-leadership offers the opportunity for bold moves due to the additional dialogue, analysis and support”27[c] that diverse leaders can bring to the table. Last but not least, a co-leadership approach can enable “critical cycles of rest and replenishment,”28 which is particularly crucial in social justice, gender equality, and sustainable development spaces.

Co-Creation

Co-creation is a participatory approach to decision making and program design that values the input and expertise of diverse perspectives to generate more innovative and effective solutions.

It involves a shift away from traditional top-down approaches in favor of a more inclusive process, where all stakeholders are empowered to speak up, contribute to the outcome, and shape the society in which they live. Writer and researcher Julian Stodd describes co-creation as a “process of social learning and collaboration that we experience within community, an iterative and refining process of editing our messages and thinking,” and further asserts that “[c]o-created change is powerful, as it’s owned both emotionally and intellectually by the team.”29 The Generation Equality Forum (GEF) Young Feminist Manifesto adds that co-creation “helps us to tap into our collective knowledge” while “chang[ing] the way we approach ownership.”30 While equitable youth engagement and co-leadership is based on the principle that young people are experts on their own lives and, therefore, best equipped to identify solutions for problems facing their communities, co-creation processes enable them to articulate, map, and build these solutions. This supports youth agency and empowers young people to become active contributors to change.

[d][e][f]

The co-creation process may not be linear, and like co-leadership models, may require a greater time or financial commitment. However, co-creation can be understood as a longer process that yields long-term solutions, as co-creation is more likely to guarantee the sustainability of programs and policies. The co-creation process helps build trust between young people and partners because everyone involved cultivates relationships throughout the project. This can lead to greater collaboration in the future. Additionally, co-creation builds ownership among those involved because the co-creators each see their own ideas represented in the project.31 Joint ownership can result in more sustainable outcomes because more people are invested in the success of a project and even long-term continuation if needed. Partners and decision makers committed to collaborating with youth must understand that power imbalances can make it difficult to reach a common language and rhythm. However, increasing youth agency can serve as both a solution to this challenge and a positive outcome.

Why Do Many Organizations Find It Difficult to Engage Youth Equitably?

Some organizations, governments, and other adult-led institutions may resist changing traditional working methods or lack trust in young people’s abilities and expertise. These institutions are often influenced by stereotypes and norms that constrain or exclude youth participation. Addressing these biases is a crucial starting point for equitable youth engagement and co-leadership.

Even when adult-led institutions seek to partner with youth, power imbalances between adults and youth can create challenges in cultivating equitable relationships. Working with diverse youth may also require more patience due to differences in languages, working styles, and interests. Still, if institutions are interested in engaging youth, they must first acknowledge and target inequitable power dynamics. To increase young people’s agency, institutions working with youth must establish a differential age approach with concrete measures to reduce gaps and asymmetry as much as possible.

Additionally, equitable youth engagement and participatory models are often misunderstood as ways to transfer work responsibilities. As a consequence, unrealistic goals are often set. Although young people are experts on their lives, this must not be conflated with professional expertise. Learning processes demand time and effort in order to create an enabling environment that allows young people to advance their skills and expertise. In addition to considering the skills of young people, the capacity and experience of adults in working with young people must also be reviewed. Adults seeking to partner with young people may need training or guidance on how to meaningfully and equitably form these relationships.

Case Study

Co-Leadership at the Generation Equality Forum and the Creation of the Generation Equality Youth Task Force

In 2021, the Generation Equality Forum (GEF), a five-year action journey to achieve irreversible progress toward gender equality, was founded on a series of concrete, ambitious, and transformative actions. The Forum was convened by UN Women and co-chaired by the governments of France and Mexico in partnership with youth and civil society. It occurred from March 29 to 31, 2021 in Mexico City, Mexico, and from 30 June to 2 July 2021 in Paris, France. This was the first time in the history of the UN that an initiative was co-designed, co-created, and co-chaired by member states, youth, and civil society, with those involved all sharing power and commitment. The Forum generated $40 billion in various financial, policy, and program commitments.

In order to represent young people in all of their diverse and intersectional identities and to facilitate youth leadership and participation in the GEF, the Generation Equality Youth Task Force (YTF) was created. The task force comprised 40 youth advocates worldwide who have dedicated their lives to advancing gender equality. It also represents diverse constituencies, including adolescents, LGBTQIA+ youth, young people living with HIV, young people with disabilities, indigenous youth, Afro-descendants, youth belonging to ethnic, religious, or caste minorities, health sector professionals, and climate justice activists. YTF is one of the co-chairs of the GEF.

While the structure for youth co-leadership was very promising, adolescents and youth also faced challenges in engaging in the GEF. Although UN Women and Member States have shown support to YTF’s leadership, there is still a power imbalance within the GEF and its other structures. Some YTF members observed that their engagements were purely tokenistic in nature and raised issues with inclusion and diversity in various GEF sessions. As a result of these concerns, young people recommended strategies for shifting and sharing power, some of which were implemented. Young people involved in the GEF also co-created the Young Feminist Manifesto32 to highlight the aims and aspirations of all the youth structures within the GEF.

Implementing Equitable Youth Engagement and

Co-Leadership

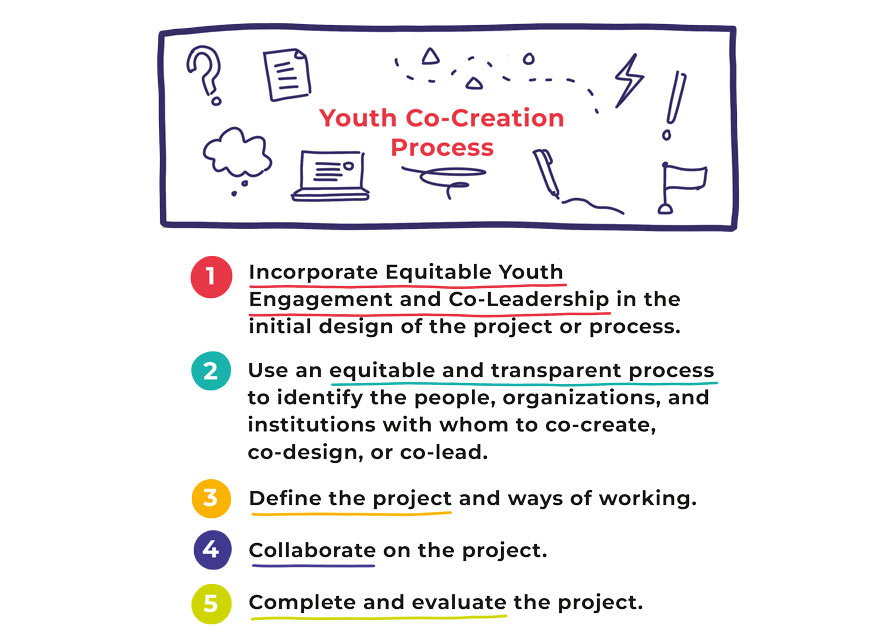

Drawing on these existing frameworks and input from young advocates, we have designed a clear and streamlined process that organizations, funders, and governments can implement when engaging youth as co-creators, co-designers, and co-leaders. This process can be applied to projects such as:

- Forming a youth advisory committee or board;

- Jointly producing a resource, publication, or research;

- Co-creating or designing programs with and for youth, including in consultations with youth;

- Engaging in participatory grantmaking programs or processes; and

- Intentional skills building for youth through trainings, knowledge sharing, mentorships, and the sharing of learning resources.

The United Nations Children's Fund’s (UNICEF) Generation Unlimited partnership notes:

“It is important to highlight that a reserved position on a Board or Committee does not necessarily translate to meaningful youth participation or genuine co-leadership. Where entrenched hierarchical decision making structures or a culture of adultism prevails, this can easily slip into tokenism. Clearly defining the young person’s role and articulating the mutual accountabilities to those in power are important prerequisites. It is important to be intentional about shifting power and to consciously address cultural norms or barriers that may hinder co-leadership. A full co-creation process that is underpinned by principles of transparency, accountability, and power-sharing can help to establish genuine partnerships between older and younger generations.”33

1. Incorporate equitable youth engagement and co-leadership in the initial design of the project or process.

- Consider at the inception of any given project whether and how youth can engage and contribute to the project.

- Identify the purpose of working with young people in this project at the outset. Avoid tokenistic inclusion and ensure that the intention is rooted in equitable engagement rather than simply meeting quotas.

- Assess the risks, especially of exploitation and abuse, posed by engaging young people in the project. Design appropriate mitigation measures to ensure the safety of young people in the project. For additional resources, Women Deliver and its partners have developed the following policies and resources regarding safety and wellness, especially the safety of young people:

2. Use an equitable and transparent process to identify the people, organizations, and institutions with whom to co-create, co-design, or co-lead.

- Establish clear criteria for selection based on the requirements of the role. Examine whether the criteria will exclude or discriminate against otherwise qualified candidates.

- Remember that young people are a diverse group made up of many different populations. A small selection of young people will not represent all youth from a given population. Take this into consideration when designing your criteria.

- Avoid tokenism in the selection process – select people because of the value they add, not only because they are a member of an identity group.

- Form a diverse review and decision makers committee that includes people from the target applicants' communities.

- Simplify the application or expression of interest process to ask only what is needed to make a selection. As the recruiting entity, do not create more work for the applicant.

- Clearly define and communicate what compensation, training, or support will be offered right from the start so that applicants can make informed decisions about their participation in a project.

3. Define the project and ways of working.

- Make time to get to know each other on a personal level and develop relationships before starting the project.

- Define the goals and objectives of the project and ensure everyone is aligned on these goals.

- Establish rules and agreements for how to work together, including the structure or format for collaboration, such as meetings or joint editing. Some additional ways of working that are important to note include:

- Ensuring accessibility by simplifying language, avoiding jargon, and providing clear definitions on any specialized terminology, as appropriate.

- Using tools that enable young people with disabilities to engage equitably in policymaking, such as screen readers and alt text.

- Being flexible – working with young people may require working differently than with adult colleagues, especially if they are in school or have other jobs, are located in low-bandwidth settings, or are in different time zones.

- Jointly determine the level of effort, work, and commitment required from each participant and ensure they are adequately compensated for their contributions.

Case Study

Women Deliver’s Approach to Honoraria for Youth

As part of its commitment to becoming an anti-racist, decolonial, inclusive, and accessible NGO, Women Deliver believes in honoring and recognizing the time, expertise, and energy given by young people in a Women Deliver-affiliated opportunity. Providing honoraria is one way Women Deliver prioritizes effective accessibility, communications, and resourcing. Additionally, providing honoraria encourages a shift from viewing grassroots, local, and/or youth advocates as beneficiaries to leaders and experts. Honoraria can support in bringing diverse voices to the table who historically have been ignored or tokenized.

Providing honoraria is just one step in a much longer journey towards ensuring equitable youth engagement, as described in this chapter, and should not be used in place of compensation for services, travel or Internet stipends, or per diem. Women Deliver offers between $25 to $1,000 depending on the scope and longevity of the project and/or activity, the amount of time and effort contributed by the recipient, the level of effort (LOE) provided by the recipient, the availability of funds, and the equitable dispensation of honoraria for project participants. Generally, the LOE is the most important factor to consider. If the LOE is limited, a smaller honorarium can be offered. If the LOE is more substantial, a corresponding increase in the amount offered is warranted. The potential safeguarding risks of providing funds, especially to adolescents, must be addressed before the provision of honoraria.

4. Collaborate on the project.

- Conduct regular check-ins for feedback and evaluate how things are going.

- Establish clear channels for open and honest communication.

- Make adjustments for accessibility and inclusion.

- Recognize the prevalence of adult-centrism in traditional organizational and institutional design and acknowledge the difficulties that young people may encounter when working alongside adults.

- Establish clear strategies that respect different learning rhythms and contextual conditions of young people involved.

- Hold each other accountable for delivering the work according to the agreed upon ways of working.

- Share information and knowledge resources transparently.

- Provide training and resources throughout the process.

5. Complete and evaluate the project.

- Acknowledge everyone involved as co-owners, including as part of the public announcement or project publication, as appropriate.

- Reflect on what worked and what did not work in the co-creation process, with the intention of mutual learning and improvement.

- Jointly determine an evaluation framework (metrics, indicators, etc.) that encourages learning, and complete the evaluation as agreed.

Case Study

Co-creation at Women Deliver: WD2023 Youth Planning Committee

In preparation for its flagship conference, Women Deliver 2023 (WD2023), Women Deliver recognized the critical importance of placing young people in decision making roles for youth programming at WD2023. The formation of a youth advisory body was included in the initial design of the creation of WD2023, to provide strategic input in the development and implementation of the Conference by co-leading and co-creating all youth programming.

The WD2023 Youth Planning Committee34 is comprised of six Women Deliver Young Leaders, six Young Leader Alumni, and six youth advocates beyond the Women Deliver Young Leaders Program. This composition was an intentional part of the design to ensure that all three groups of youth constituents were represented equally on the Committee. Women Deliver created comprehensive terms of reference (TOR) for the Youth Planning Committee that included background information, the purpose of the Committee, key responsibilities, compensation and technical support provided, qualifications, and a description of the application and selection process. This TOR was posted on Women Deliver’s social media and shared with Young Leaders and youth networks to ensure an open application process. After the four-week application window closed, a diverse review committee of Women Deliver staff, Regional

Consultants, and members of the Young Leaders Alumni Committee reviewed the applications using a common review matrix. Each application was assessed by 2-3 reviewers. The final selection was made based on reviewer comments and efforts were made to ensure a regionally and demographically diverse Committee.

The WD2023 Youth Planning Committee held its first meeting in the fourth quarter of 2022. The first meeting focused on relationship building, aligning the responsibilities and expectations of the Committee members, and co-creating ways of working. For example, it was decided that monthly meetings would take place at two different time options to account for the large span of time zones in which members live.

The WD2023 Youth Planning Committee met monthly from October 2022 to July 2023 and carried out much of its work in specific Subcommittees based on the deliverables the Committee was charged with creating. Women Deliver staff and Regional Consultants regularly met with individual or small groups of Committee members to check in, address concerns, and move the joint work forward. Committee members worked collectively to design WD2023 youth programming, which was still in formation at the time of this publication’s drafting.

Applying Equitable Youth Engagement and Co-Leadership to Policymaking in Government

Governments must engage young people in policymaking and programming to ensure responsiveness to their needs. This can also lead to additional funding for youth-led initiatives and youth programming, and providing this funding at the national level is the most sustainable long-term approach to ensure ownership and continuation of these programs.

Given their formal and sometimes bureaucratic ways of working, governments need institutionalized mechanisms through which young people can equitably engage in policymaking and program development. Some specific ways governments can institutionalize youth engagement meaningfully and equitably include:

- Establishing formalized youth advisory boards within specific government ministries or providing young people with a platform to co-create with policymakers.

- Appointing young people to public offices, committees, and other governing bodies where key decisions are made, particularly if the issues affect youth. However, avoid a tokenistic approach in which young people are only selected because of their age; rather, appoint young people to roles because of their expertise and lived experience.

- Ensuring that budgets allocated for youth programming are not cut or deprioritized when there are budget realignment measures or situations requiring austerity measures.

- Developing tailored training for young people who are engaging in policymaking to build their capacity and knowledge, based on the actual needs and requests of young people. This can even start with school-age young people who may run for school councils or participate in programs such as Model UN or mock Parliament.

- Partnering with community-based and youth-led organizations that have expertise in working equitably and meaningfully with young people.

- Developing a comprehensive whole-of-government approach to equitable youth engagement and co-leadership that applies across ministries and agencies. This unified approach will ensure all agencies are working together and advancing the same values as it relates to youth engagement. This makes it easier for young people to engage and participate in government mechanisms, as well as results in better policies and programs.

In addition, governments should not only focus on innovative ways to engage young people in policymaking but also think about how they work with youth-led organizations. This means listening to youth-led organizations and understanding how they want to partner with the government and what resources and support they need.

Case Study

Equitable Youth Engagement and Co-Leadership in the Government of Norway

In 2019, the Norwegian government introduced a new law, the Local Government Act,35 which mandates the establishment of youth councils in all municipalities in Norway to provide young people with a voice in local decision making processes. Youth council members can hold office for up to two years and must be younger than 19 at the time of election. The law also requires that the municipality must ensure that young people are informed about the decisions made by the municipality and the reasons for those decisions. In 2022, the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs (Bufdir)36 developed a guide for newly created youth councils in consultation with several more established youth councils in Karasjok, Alta, and Hammerfest, emphasizing the role youth councils play in promoting youth participation in decision making processes. The guide provides examples of best practices for youth councils, including how to engage young people in recruitment, how to facilitate meetings, and how to establish partnerships with local government officials.

How do we measure equitable youth engagement? What does successful equitable youth engagement look like from the perspective of young people?

Measuring equitable youth engagement and co-leadership can be tedious and challenging. The number of young people involved in a project or activity can be a good starting point, but it is important to go beyond the numbers and consider the quality and depth of their involvement. Asking young people for feedback on their experiences and evaluating the long-term impact of their involvement can provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of youth engagement efforts. Assessing the diversity and inclusivity of engagement activities can guarantee that every young person has an equal opportunity to participate and contribute.

Successful equitable youth engagement from the perspective of young people requires being treated as equal partners and decision makers in projects or programs that directly impact their lives. This means that young people should have a say in the planning, design, budgeting, and implementation of initiatives, as well as receive the necessary support and resources to contribute meaningfully. Decision making processes must be made accessible to all young people without coercion and discrimination.

Offering financial, logistical, and emotional support and discussing the needs of young people in advance is not only crucial to equitable youth engagement, but it’s also an ethical imperative. Young people bring valuable knowledge and lived experiences to the table and should be compensated like any other experts. Supporting them with stipends and honoraria, paying for their time, and providing them with contracts are just a few examples. It is vital to recognize the value of their time and effort.

Citations

22a) Organizing Engagement. (n.d.). Ladder of Children’s Participation. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://organizingengagement.org/models/ladder-of-childrens-participation/

22b) Youth Do It. (n.d.). Flower of Participation. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.youthdoit.org/themes/meaningful-youth-participation/flower-of-participation/

22c) Women Deliver. (n.d.). Meaningful Youth Engagement: Sharing Power, Advancing Progress, Driving Change. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://womendeliver.org/publications/meaningful-youth-engagement-sharing-power-advancing-progress-driving-change/

23. Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1229039

24. Honneth, A. (1995). The struggle for recognition: The moral grammar of social conflicts, trans. Joel Anderson, Cambridge: Polity.

25. AMREF Health Africa. (2022). Adolescent and Youth Strategy. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://amref.org/ethiopia/download/adolescent-and-youth-strategy-2021-2022/

26. O’Malley, D.L., Johnson, R. (2022) Mosaics & Mirrors: Insights and Practices of Feminist Co-Leadership. Feminist Co-Leadership. Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.feministcoleadership.com/

27. Ibid

28. Ibid

29. Stodd, J. (2013). The co-creation and the Co-ownership of Organisational Change. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://julianstodd.wordpress.com/2013/11/29/the-co-creation-and-co-ownership-of-organisational-change/

30. Gender Equity Forum. (n.d.). The Young Feminist Manifesto. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://gefyouthmanifesto.wixsite.com/website

31. Norwegian Agency for Exchange Cooperation (Norec). (2022). Partnership – Just Another Buzzword? Retrieved May 2, 2023, from https://www.norec.no/en/news/reports/partnership-just-another-buzzword/

32. Generation Equality Forum. (n.d.). The Young Feminist Manifesto. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://gefyouthmanifesto.wixsite.com/website

33. Generation Unlimited. (2022). Intergenerational partnerships for transformative change: A learning brief. New York, USA. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.generationunlimited.org/reports/intergenerational-partnerships-transformative-change

34. Women Deliver Conference 2023. (2022). Youth Engagement at WD2023. Retrieved April 28, 2003, from https://www.wd2023.org/youth-engagement-women-deliver-2023-conference/

35. Norway Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development. (2021). The Local Government Act. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/the-local-government-act/id2672010/

36. Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS). (2022). Training of Youth Councils for Youth Councils. Retrieved May 2, 2023, https://www.ks.no/contentassets/a7a55770037c4ac6b0c4aefffa01b636/KS-Hefte-Undomsmedvirkning-og-ungdomsraad-ENG.pdf