Building Resilient and Responsive Health Systems: A Q&A with Michael Myers

Michael Myers is the Managing Director at The Rockefeller Foundation. He leads the Foundation’s global health work including its Transforming Health Systems initiative and the campaign for universal health coverage. He also coordinates strategies for the Foundation’s work in the United States with a focus on building inclusive economies in cities.

Michael Myers is the Managing Director at The Rockefeller Foundation. He leads the Foundation’s global health work including its Transforming Health Systems initiative and the campaign for universal health coverage. He also coordinates strategies for the Foundation’s work in the United States with a focus on building inclusive economies in cities.

There are multiple benefits to building health systems that provide a continuum of care for girls and women. First and foremost, it saves lives and, subsequently, money. While governments bear the greatest responsibility to ensure that girls and women have access to comprehensive healthcare, everyone has a role to play to reduce barriers and promote the health and wellbeing of all. In the interview below President/CEO of Women Deliver Katja Iversen and Michael Myers explore the importance of Universal Health Coverage, Planetary Health, and more.

In health, we need systems that are not just a series of silos that fall like dominoes when they face crises. We need networked systems in which all elements are connected.

Katja: For the past decade, The Rockefeller Foundation has focused on building up the resilience and responsiveness of health systems. We know that strong health systems have networks of clinics, labs, trained workers, and reliable supply chains, but resiliency and responsiveness is a new topic. Why is this so important to The Rockefeller Foundation? And more specifically, why is this so important for the advancement of the world’s girls and women?

Michael: We live in an increasingly unpredictable world. In health, we need systems that are not just a series of silos that fall like dominoes when they face crises. We need networked systems in which all elements are connected. In this way, the systems can adapt even when the unexpected comes—they can bend, but not break. We find that systems that prepare well for times of crisis also come to function better in times of calm. This is critically important to girls and women specifically. You don’t want a health system that gets so overwhelmed by a health shock that it can no longer tend to maternity or neonatal care in times of crisis.

Katja: At Women Deliver, we know that healthy girls and women are the cornerstone of healthy societies and we extol the benefits to building health systems that provide a continuum of care for girls and women. But the moral and economic costs of failing to invest in disease prevention, screenings, vaccinations, and integrated health systems are staggering. To stop these costs, governments need to invest on the front-end. Can we innovate health financing through Universal Health Coverage?

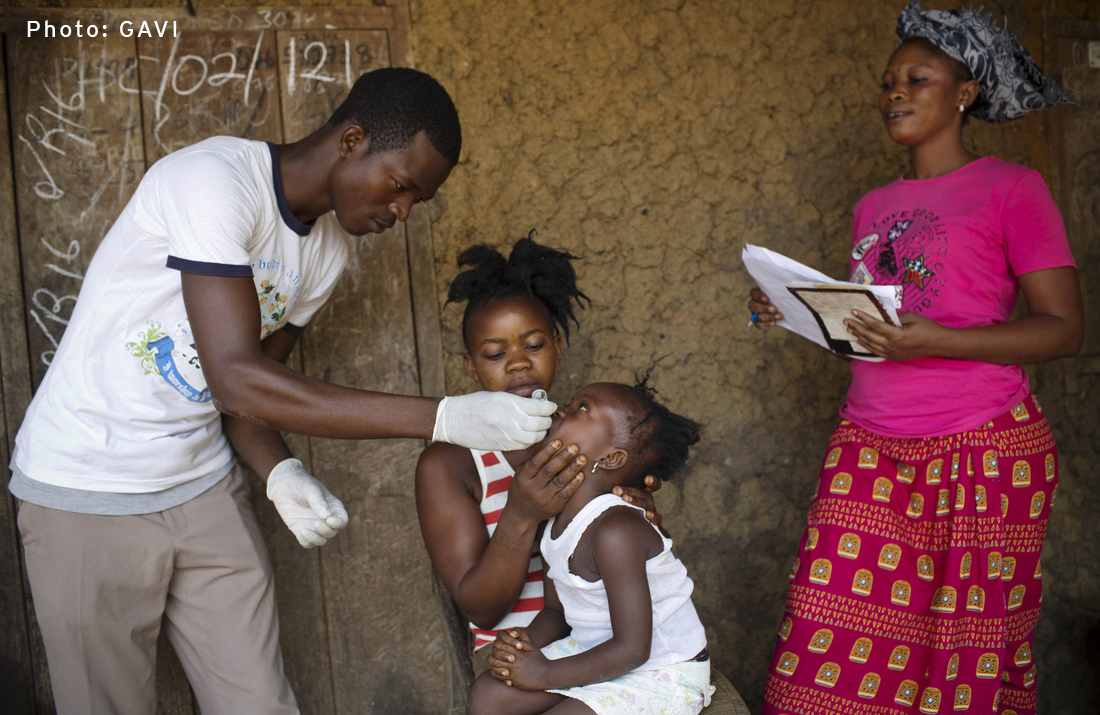

Michael: Those of us who work on health issues seem to constantly re-learn an important lesson: people live in communities. Investing in health at the community level, with prevention activities, screenings, and vaccinations, as you mention, not only keeps people healthier but also helps prevent epidemics.

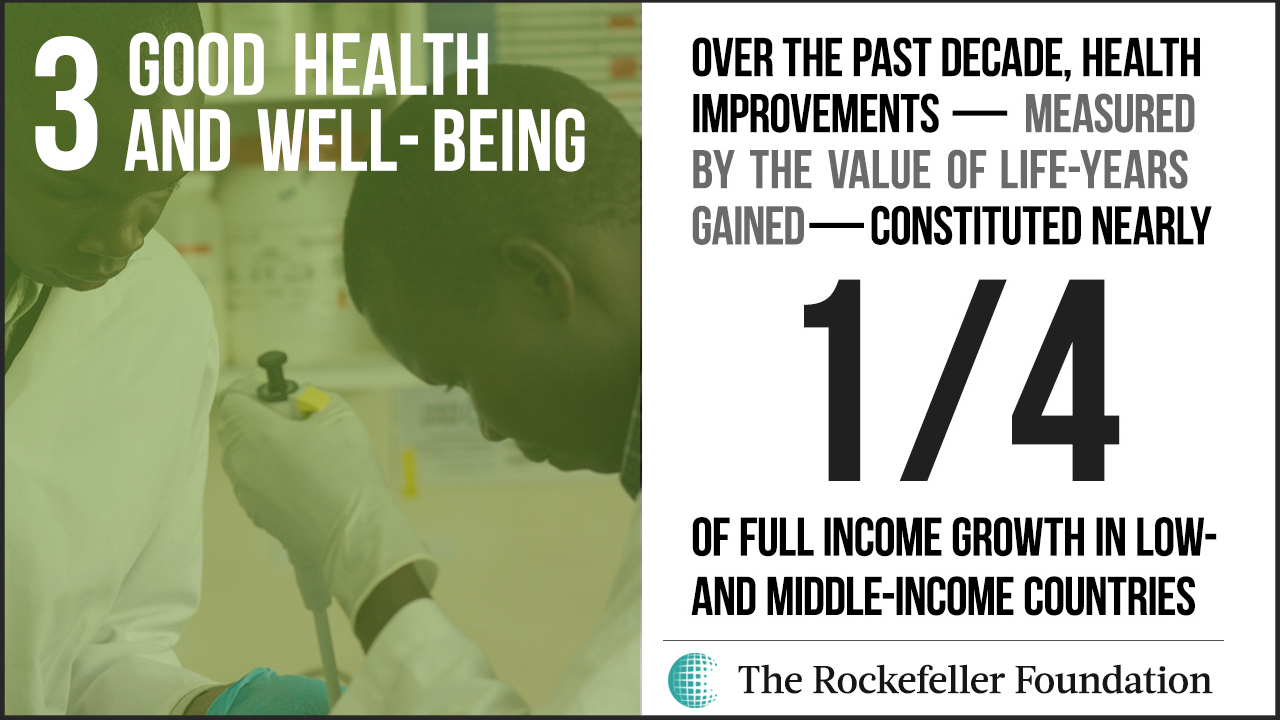

One thing to realize is that these front-end health investments also enable people to be more productive, creating a real return on these investments in terms of economic growth. In fact, some 24 percent of economic growth from 2000 to 2011 was due to better health outcomes. There are also other investments outside the health sector that have huge health benefits. For example, one of the greatest returns on investment in health is girls’ education.

We have seen the dramatic consequences of failing to invest in health in the form of loss of life in situations such as the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. That also had enormous economic and social consequences as schools and businesses closed, trade slowed, and tourism stalled.

So there is a clear health case for these front-end investments, but also a powerful economic argument as well.

Katja: When it comes to global health, it seems we are living a sort of paradox. On the one hand, life expectancy has soared, maternal and child deaths rates are down, education initiatives are seeing wide success, and many of the world’s poorest people are transitioning to better lives. But all of this progress is happening alongside climate change and serious environmental degradation. Can you help contextualize this from a human perspective? What does our current trajectory look like for, say, a 7-year-old girl in Bangladesh?

Michael: I believe that the paradox plays out in at least two different ways.

First, as nations develop economically and per capita income goes up, health challenges change. The health issues facing a 7-year-old girl in Bangladesh can change from a focus only on infectious diseases to include non-communicable conditions as well. With greater prosperity comes greater obesity, for example, and with that could come heart disease and diabetes. It becomes very important for the girl in this example to adopt a healthy lifestyle early in order to live a long and healthy life.

Second, there are the effects of a degraded environment. The exploitation of earth’s natural systems has led to huge economic growth. Our life expectancy has increased exponentially due to the exploitation of natural resources for our energy, food, and other benefits. However, we are now learning that more and more diseases and deaths can be traced to environmental causes. More people die today due to outdoor air pollution than HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria combined. So keeping this hypothetical 7-year-old healthy in the future is not just a medical challenge, but an environmental one as well.

"We must get to a point very, very soon in which we no longer have separate agendas in health and justice and climate change and economic development and so on."

Katja: The global development community is beginning to recognize the connections between population health and environmental health, but The Rockefeller Foundation has made the conscious choice to pursue solutions in this area. Can you give us a top-line definition of planetary health and your hopes for it?

Michael: Planetary health is viewing the environment and health as one problem to solve, and not as issues to be tackled separately. Planetary health brings together people from a wide variety of disciplines and perspectives to address this problem—from health, of course, but also from the environmental field, agriculture, economics, policymaking, technology, and more. We need integrated thinking and approaches combining all of these disciplines to steward earth’s natural systems in ways that protect our health. And a desire for good health can also lend momentum to environmental work.

Katja: Working on planetary health is especially urgent for girls and women, who are tasked with water and fuel collection, work in agricultural production, and are most displaced by climate change. How can our community of health, equality, and justice advocates push the agenda forward, together?

Michael: We must get to a point very, very soon in which we no longer have separate agendas in health and justice and climate change and economic development and so on. The Sustainable Development Goals present an opportunity and a challenge to work together across sectors toward a common goal, as articulated in the preamble, “to free the human race from the tyranny of poverty and want, and to heal and secure our planet.” We don’t really know how to do this very well—yet. But I think the communities of health, equality, and justice advocates can model a way to do this, to push forward not only their agenda, but other agendas that span the SDGs. It’s by working together that we will see all boats rise.